In 2011, Environmental consultancy firm ADAS conducted research into the development of sustainable food and beverage supply chains by interviewing senior staff at some of the world’s leading companies. Mark Holmes, a sustainable food/beverage specialist at ADAS was pleased to discover excellent examples of supply chain activity but in this article he describes how improvements in areas outside of a company’s direct control can be more difficult and represented the next big challenge for the industry.

Summary

All of the companies contacted in the course of this research have comprehensive programmes in place to improve the sustainability of their own operations. Responsibility for sustainability is clearly identified at board level and is now embedded throughout their organisations. Corporate responsibility programmes are well under way and have already delivered well-documented benefits.

Supply chain sustainability is more complicated to address, particularly if the number of suppliers is large and multi-layered. However, the opportunity for organisations to create beneficial effects through their supply chains is enormous. Tesco, for example, has found that the carbon footprint of its supply chain is ten times the size of that for its own activities. As a result, Tesco has recently committed to a 30% reduction in its supply chain emissions (CO2 equivalent) by 2020 relative to a 2008 base level.

It is clear that the major companies in the food and beverage industry recognise the threat of climate change and fully accept their responsibility to help reduce its effects. They understand that the world’s booming population, combined with water scarcity in many regions and a dependence on irrigated agriculture, place a heavy burden on the world’s capability to feed itself.

The consensus is that it is not good enough to rely on consumer choice; major food and beverage companies need to take the lead, to exploit the benefits of size and to set examples for others to follow.

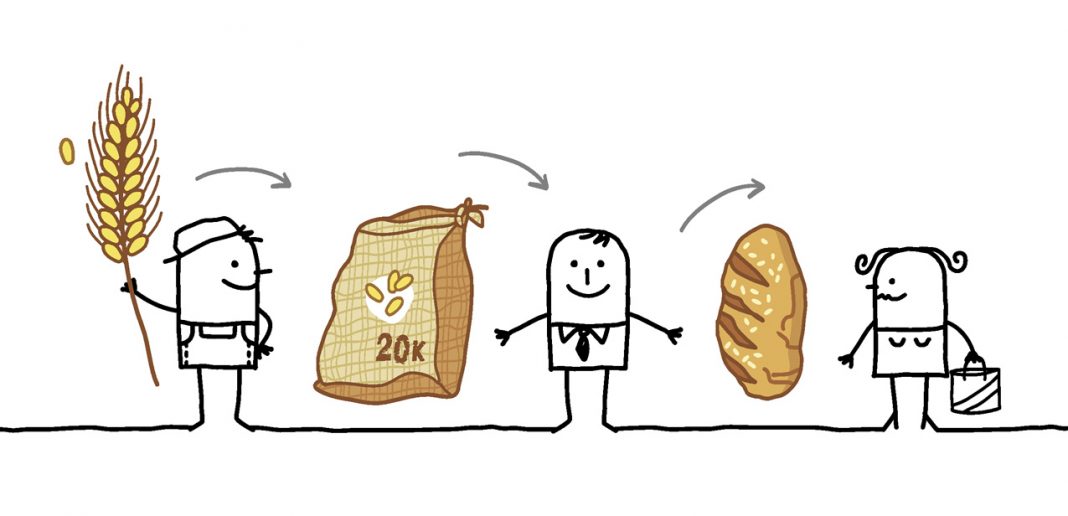

What is supply chain sustainability?

There is no legal or universally accepted definition of ‘sustainable food’. This is fundamentally because the sustainability of food means different things to different people and represents a calibrated balance of emerging food issues about human health, economic, environmental and social concerns faced by individuals or society as a whole.

Bob Carss, Group Environment Manager at VION UK described sustainability as “being a bit like world peace – a very large concept and even if we never quite get there; it’s the best path to take.”

Each company’s definition of a sustainable supply chain is dictated by the business environment in which it operates and the nature of the raw material that it procures. For some, such as those in the meat industry, sustainability is a balance of high animal welfare standards, competitive costs and minimisation of environmental effects. Others include health and safety and the support of rural communities. These issues are all intermingled, but the key objectives are to create a responsible and resilient supply chain that addresses the threat from climate change by reducing GHG emissions and adapting to challenges such as increased water scarcity.

The term sustainability in the supply chain is in its infancy and organisations are tending to look for the lowest hanging fruit. Often, this is cost reduction such as energy efficiency, but it can also be the efficiency of other resources and waste reduction.

The one common theme amongst all the respondents in the research is a desire ‘to do the right thing’ for the business, customers and future generations.

What are the drivers?

There are a wide range of drivers for action on supply chain sustainability. All of our respondents have been busy getting their own houses in order and are now at various stages of development in cascading sustainability through their supply chains. A number of factors were listed as the major drivers for this work:

- Climate Change – the science is accepted, which in turn is driving government and industry to take action

- Business leadership – company bosses are driving sustainability initiatives because it makes good business sense

- Better understanding – improved knowledge of the supply chain delivers a more secure supply chain

- Trust – consumers expect the major suppliers to make sustainability choices on their behalf

- Risk reduction – ensure security of supply and limit vulnerability to climate change

- Cost reduction – achieve sustainable productivity by optimising resources such as energy, water and fertilisers whilst also reducing waste

Interestingly, none of the respondents mentioned regulatory drivers; however, the Environment Agency recently published a ‘Greener Business Report’ which said: ‘Businesses increasingly use environmental credentials as part of their brand. We want businesses that make these claims to show good environmental stewardship throughout their supply chains, and we will lighten the regulatory burden on businesses who take this responsibility seriously.’

What are consumers’ expectations?

There is a general impression that consumers expect well known brands to do the right thing; to ‘choice edit’ goods and services on their behalf. Jessica Sansom, Head of Sustainability at Innocent, supports this by saying: “We can’t sit back and ask consumers to be the catalyst for change – the issues are far too complex to ask people to include them in their purchasing decisions. There is definitely a role to keep consumers aware and engaged but it’s no good thinking that consumer choice will solve the problem, because it won’t.”

Sustainability is clearly one of the biggest issues facing the food industry. There is an expectation from consumers that global companies act responsibly, protecting precious resources and adopting sustainable practices.

Tesco is busy putting carbon labels on many of its major products. Their Climate Change Manager, Hannah Clare says “We are putting more carbon labels in Tesco than any other store because consumers want this information. We have labelled over 100 products but we have measured the carbon footprint of 500 and will footprint a further 500 by the end of the year.” Hannah concedes that a footprint value means very little to most consumers at the moment. However, she says “The fact that we have worked on a product’s carbon footprint demonstrates that we are working on the sustainability of that product. In addition, we supply information to help the customer make choices based on sustainability. For example, next to the carbon footprint logo on our own-brand orange juice we explain that concentrated juice has a lower footprint.”

What are the main issues?

Security of the supply chain is a major issue and scarcity of resources is a serious threat. Water is becoming a major issue in many regions of the world and climate change, combined with population growth, will only make this situation worse. Dole, with 2009 net revenues of $6.8 billion, is the world’s largest producer and marketer of fresh fruit and fresh vegetables. Their VP of Corporate Responsibility and Sustainability, Sylvain Cuperlier says “Dole’s sustainability strategy is built on four pillars – carbon footprint, water use, soil conservation and packaging. This is because climate change represents a threat to our greatest assets: people, farms and the environment.”

Many of the respondents choose to source British food in response to consumer demand – and often pay a premium for doing so. For instance, McDonald’s UK only uses British and Irish beef in its burgers. However, issues such as carbon footprint and animal welfare complicate the picture. Peter Mitchell from OSI Food Solutions, says “The carbon footprint of a suckler beef herd roaming the fields and grazing ‘naturally’ is greater than a more intensive indoor beef system. However, the welfare of the outdoor system is perceived by many to be better, so there is conflict between perceived animal welfare and carbon emissions.” A similar situation exists for outdoor pigs and poultry.

McDonald’s has recently highlighted the potential role for beef from the dairy industry to contribute to more sustainable British agriculture.

In the pig sector, Supply Chain Development Manager at Tulip, Mark Haighton, says “Over the last 12 years the UK sow herd has almost halved due to poor producer profitability. It can be argued that the costs associated with higher welfare pig production have made the UK pig industry less sustainable than other countries’ industries where animal welfare is less of a concern. Furthermore recent increases in feed raw material prices are exacerbating the issue of non-sustainable pig production, not just in the UK but globally.”

The ability of a company to influence its suppliers is strongly affected by the proportion of the suppliers’ sales that they represent. The level of influence is also affected by the number of tiers within the supply chain and the number of suppliers in within each tier.

Selling 15 million loaves per week, Warburtons does not have a very long shopping list, but it does buy a lot of wheat directly from 320 UK farmers. “It is therefore strongly in our interest to protect the financial well-being of these farms,” says Sarah Miskell, Warbutons’ Director of Sustainability. “We pay a premium for the best quality wheat and we go to great lengths to ensure that our wheat or milled flour is not mixed with any other.”

Work on sustainability in the Warbutons supply chain with just 320 UK farms is relatively simple. In contrast, Dole, with many thousands of growers, often small family farms, in different regions around the world, has a significantly greater challenge. However, a partnership approach involving supplier engagement and the sharing of best practice was a common theme amongst most respondents irrespective of supply chain length or complexity.

In the examples cited above, primary producers are working for a dedicated supply chain so that the provenance of the products is clear and a relationship between every step in the supply chain has been established. In such circumstances sustainability improvements are relatively simple to enact. However, when commodities are purchased on the open market, sustainability is more problematic.

Solutions to sustainability issues with commodities are currently being developed. For example, with the support of Rainforest Alliance and 4C, it is now possible to purchase green coffee that is compliant with the internationally recognised 4C sustainability standards. It appears, therefore, that sustainable commodities can become available when there is concerted effort to establish an effective certification scheme.

What is being done in the supply chain?

The level of activity on sustainability in the supply chain varies from company to company and is clearly an activity still in its infancy. For example, one of the major companies contacted in the research declined to participate for the quite understandable reason that they are currently establishing a baseline for their supply chain sustainability so that targets can be established in the (near) future.

Many of the respondents are using tools such as carbon footprinting to understand the emissions from the supply chain to indentify hotspots of where to focus improvement strategies. This work includes both organisational and product footprints being undertaken with a variety of methodologies, which will make it difficult for observers to compare one company with another. These include for example, the Greenhouse Gas Protocol and PAS 2050 a method for measuring the carbon footprint of products.

However, as Sarah Miskell says “It’s better to get started than to worry about whether the method is perfect – once you start conducting footprinting work you soon discover the major issues. For us, we learned that 50% of our carbon footprint comes from Nitrogen based fertilizers, so efficiency of nitrogen use has become a major objective for us in cooperation with our farmers.”

Many of the respondents included ‘Retailers’ in the list of drivers for supply chain sustainability and Tesco, for example, has written to 1200 of its suppliers asking them if they can/want to commit to the 30% supply chain emissions reduction target. 50% have come back with detailed responses and a further 25% have said they are keen to be involved.

Supplier engagement is a common theme and all respondents commented on the need for partnership – providing encouragement for sustainability improvements. For many, this meant sharing best practice; not just down the chain, but also from producer to producer and up the chain.

Early work on supply chains often reveals quick financial wins – particularly energy and waste reduction and this can serve as a major incentive for subsequent work, even if the wins become harder to reach.

The old adage ‘if you don’t monitor it; you can’t manage it’ is certainly true for supply chain sustainability. Measures need to be established so that targets can be set and most companies have a set of criteria that potential suppliers must meet.

McDonald’s has created an Environmental Scorecard that collects data from manufacturing suppliers on four key indicators – energy, waste, water and air. This helps to incentivise improvements, however, suppliers also need help and advice on ways to improve, so many of the respondents provide on-farm technical experts. In addition, most companies are running supplier workshops and offering a wide range of other sources of information including web sites, literature, site visits and case studies.

Summary

The experiences of the ADAS sustainability services team have shown that the resilience of agricultural commodity supply chains is severely affected by issues relating to energy, the risks from climate change such as water availability, and other threats from new pests and diseases etc.

All food and beverage companies ultimately depend on agricultural commodity supply chains that can deliver a consistent product to the desired specification at the right cost.

It is clear from the interviews that environmental risk is a common concern affecting supply chain resilience. However, supply chains offer enormous potential for improvement so it is encouraging that a great deal of work has begun in this area.

The five key ingredients for a sustainable supply chain are as follows:

- Leadership: committed to a sustainable supply chain strategy

- Measurement: establish baseline performance and then set measurable goals

- Partnerships and engagement: adopt a partnership approach with suppliers, share best practice and reward sustainability champions

- Incentives: encourage improvements rather than penalising poor performance

- Transparency and communication: ensure transparency, communicate sustainability targets/performance and avoid ‘greenwash’

Implementing improvements in supply chain sustainability is simply an extension of ‘doing the right thing’ – a factor that many of the respondents cited as contributing to their longevity (more than100 years in some cases).

Whether the world’s politicians manage to agree binding emissions reduction targets or not, the food and drink industry is focused on sustainability, not least because as the effects of climate change begin to bite, the industry has become a barometer for mitigation and adaptation to the impacts of climate change.

It is evident that the development of sustainable food supply chains is one of the major challenges for food and beverage companies. The opportunity to meet customer needs, reduce costs, ensure security of supply and manage risk is not just a project for short-term gain, but an investment in long-term resilience – a challenge that cannot be ignored.

Ends

Words: 2,476

Acknowledgements: The author would like to express his gratitude to the following companies who helped with the research that lead to the development of this article:

Dole Group

Innocent Drinks

McDonald’s

OSI Food Solutions

Tesco

Tulip

VION

Warburtons